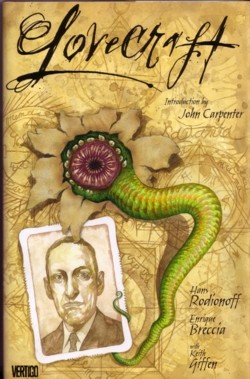

Lovecraft: The Graphic Novel

Originally for Raw, New Things #12, 5/2/2004

Lovecraft is a Vertigo publication, currently in hardcover. Vertigo’s current publication scheme means that it will definitely be some eighteen months before this atrocity is out in a less expensive paperback, and I can only say that you should buy it only if you’re desperate completist.

Why oh why are comic writers so obsessed with Lovecraft’s sex life? Grant Morrison, and now this Hans Rodionoff keep hammering on about Lovecraft’s supposed fear of women and Lovecraft’s monsters being vaginal symbols. When the did it become acceptable to believe the secondary source more than the primary? Can anyone who has read the Monarch notes on Lovecraft confirm these as a likely source of King’s inaccurate statements in Danse Macabre?

I’m all for a little creative licence when putting hyptheticals into peoples’ lives. Unfortunately, Hans Rodinoff does it the grace and subtlety of a rhinoceros in the mating season. The story seems to come from the ‘shake-n-bake’ theory of writing; put a bunch of elements from Lovecraft’s life in a bag, shake vigorously, and reassemble with whatever glue seems to work with the narrative. If nothing else, this book has given me a great appreciation for the deft work of Tim Powers, who very neatly insinuates his fictional reality into the lives of his real protagonists, rather than hammering it in, forcing reality to bend to accommodate the needs of the preconceived story. And even this would have been forgivable if the story had been remotely interesting. Which it isn’t. The great insult to Lovecraft’s life is the pure mayhem done to the documented dates of Lovecraft’s life. My God, the dates.

The primary action of Lovecraft takes the protagonist from age five to his separation from Sonia Lovecraft, which happened, according to the text in 1925 (or 1926, for those of us who know anything about the real Lovecraft). There is passing reference, during the period in which Lovecraft lived in New York of his correspondence with Robert Howard, which didn’t start until 1930. An early scene involves Lovecraft meeting his publisher Edwin Baird in New York before he even meets Sonia, and correcting Baird’s pronunciation of Cthulhu as "Shuthoolhoo". The graphic novel ends with Lovecraft’s return to Providence in "1925" (rather than 1926, as happened in reality) and "Call of Cthulhu" was not published until Lovecraft had returned to Providence. Lovecraft reads a copy of "Dreams of the Witch House" to the Kalem club, although the story wasn’t written until some seven years later. ‘Dunwich Horror" is referred to, although it isn’t written until 1928.

Sonia Lovecraft uses the expression "Blessed Savior" an unusual expression for a Russian Jew. She is shown meeting Sarah Lovecraft, who died in May 1921, fully two months before Rhienhart Kleiner introduced H.P.L. to his future wife at a NAPA convention.

So skip it. This entire graphic novel is a putrescent mess in the same vein as the utterly forgettable Shadows Bend, for people whose conception of Lovecraft is in no way based in the reality of the man’s life. If it weren’t so expensive, I’d send the author of the H.P. Lovecraft Encyclopedia in utter disgust. Even more depressing, this graphic novel made the front page of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch’s entertainment section on February 17th, in which the reviewer holds Lovecraft up as a fine example of what graphic novels can accomplish. Please, please, please, Mr. Joshi, find a way to have Lovecraft: A Life brought back into print. The world desperately needs to understand that Howard Phillips Lovecraft was an unusual man whose creativity was so extraordinarily marvelous that to say he took his ideas from some sort of parallel reality is a prosaic disservice to him.